Blog posts are written by project team members. Topics range from conferences we attend, musings on current affairs of relevance, internal project findings and news and more succinct content which can be found in our Digital Humanities Case studies or project related publications. Blog posts will mainly be posted in English but will from time to time feature in the language of the project team member’s preference, since we are a multilingual bunch! Happy reading!

Go out wearing masks! A media history of face masks

This post is available in its original French version on Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/12052020/sortez-masques-histoire-mediatique-du-masque-de-protection

Ever since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the issue of face masks has been hotly debated in France: initially recommended before being considered unnecessary in the absence of symptoms, they were eventually adopted and even made a requirement on public transport. But what about during past epidemics? Did face masks have to be worn then?

Right from the first reports of the outbreak in France back in January 2020, a flurry of health advice – not all of it verified – has been proffered to help communities actively combat the disease. Among the hygiene measures advocated in countering the virus, wearing face masks has sparked controversy. Although they were initially ranked among the protective measures outlined by the Ministry for Solidarity and Health to curb the outbreak at the end of January 2020, opinion has since changed and they no longer feature in official recommendations. Considered by some to be "unnecessary for any asymptomatic individuals", counterproductive and even dangerous because of how tricky they are to use properly, but by others as a logical addition to the applicable measures, face masks have ended up being expressly embraced in public and became compulsory on public transport from 11 May 2020. These changes in opinion seem to be partly driven by stock management, but they also call to mind the debates on the effectiveness of masks during outbreaks that can be found in the press archives from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Indeed, although broad-scale use of the face mask may strike us as an unprecedented preventative measure owing to its poignant visual effect (with the mask representing a hitherto invisible threat and inducing a sense of fear), it has often been recommended when health conditions made it necessary. What were the recommendations concerning face masks in centuries past, and what was the French population’s reaction to them then? Let’s find out more about this measure that is less original than you might think.

A recommendation that has been around a long time

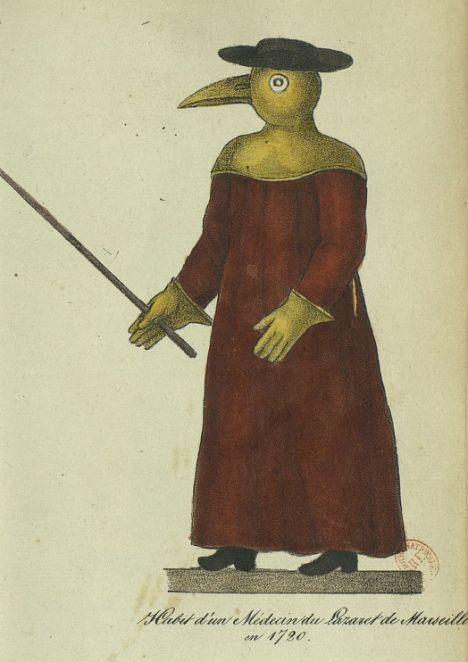

As far back as the 17th century, the famous "beaked mask", filled with plants known for their disinfecting properties, had already been dreamt up by Charles de Lorme to protect plague doctors from airborne contagion. Over time, and with each new outbreak, filtering devices were refined, and it was in the latter half of the 19th century – when medical research was benefiting considerably from Louis Pasteur’s work – that face masks began to be worn in hospital settings. They have been systematically advocated for ever since, first among health workers and then more generally for anyone likely to come into contact with droplets of mucus or saliva containing patients’ germs.

On 13 May 1915, an article in LeTemps described this innovative “small device”, attributing its invention to Dr Henrot in 1868:

“A respiratory mask. — It was designed in 1868 by Dr Henrot to ward off the danger of contagion from certain infectious diseases via the airways – diphtheria, for example. It is comprised of a framework sealing in the nose and mouth, which is closed on the outside by two metal cloths between which cotton discs are placed. All the infectious germs remain attached to these discs and the air is thus rigorously filtered. A small, very simple and highly sensitive valve lets out the inhaled air. The whole of this small device is made of aluminium, so it is very light, and is easy to wear like spectacles.” (Le Temps, 13 May 1915, p. 4)

In 1895, the same Dr Henrot (as mentioned in an article of Gil blas, 27 September 1895, p.2), suggested equipping the privates in Madagascar with face masks to protect them from noxious fumes. Although this idea has since gained ground, not least during World War I, back then it was considered comical if not downright ridiculous:

" ... What could be more dumbfounding than this proposal of Dr Henrot, to equip our troops with a mask intended to filter air and rid it of its putrid fumes, just like those mediaeval doctors did, thinking that they could avoid catching plague with the help of a grotesque suit? And to think that this proposal was presented to the Academy of Medicine, and that it warranted a discussion!...” (Excelsior, 28 February 1916, p. 2/12)

Throughout the 20th century – especially during the flu pandemics of 1918 and 1929 – and until last April, the Academy of Medicine was in favour of the antiseptic mask and had strongly recommended its use. The measure is by no means new, as we can see in these conclusions, which still stand today:

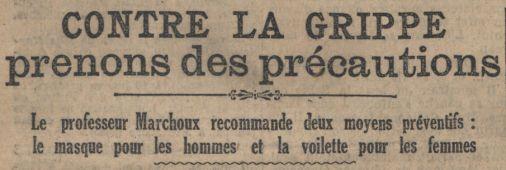

"The recent conclusion, adopted by the Academy of Medicine at Dr Bezançon’s proposal, recommending that masks be worn to avoid the spread of flu among health staff, is not new. The face mask first emerged many years ago […] Would it be too complicated to wear over the mouth and nose a few layers of gauze-like fabric held by a wire framework, just like we wear spectacles – or even more simply, to wear a thick hat veil?” (Le Petit Parisien, 27 October 1918)

"At the Academy of Medicine’s session yesterday, the knowledgeable Professor Marchoux made an announcement of the greatest interest and relevance today; he recommends, particularly for doctors and hospital staff, wearing a light structure, hat veil or mask, in addition to spectacles, on the face, so as to protect against the projection of septic droplets when flu patients under treatment sneeze, cough or speak.” (Le Journal, 13 February 1929)

"In order to limit the risk of directly transmitting the virus via droplets projected when speaking, coughing or sneezing, wearing an anti-projection mask covering the nose and mouth, designed to retain these sputters and stop them dispersing in the immediate environment, has been recommended in a recent paper of the National Academy of Medicine […] To be effective, the wearing of anti-projection masks should be widespread in the public space.”

Wearing a mask: prompting scepticism or antiseptic?

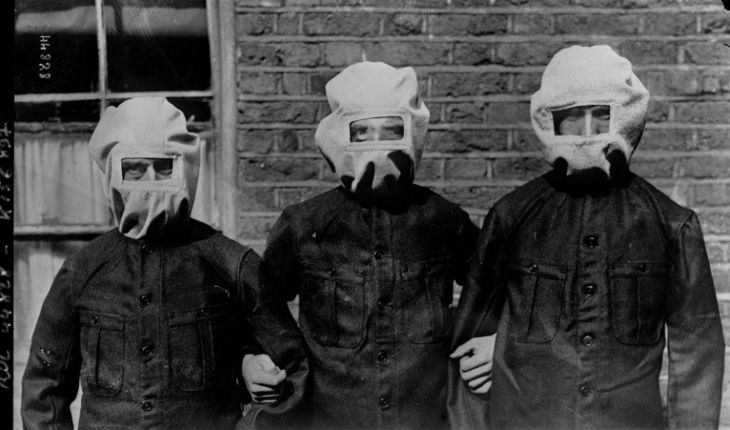

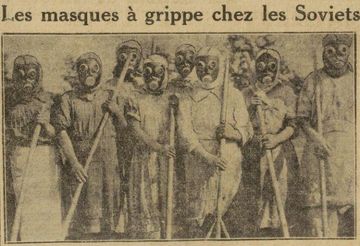

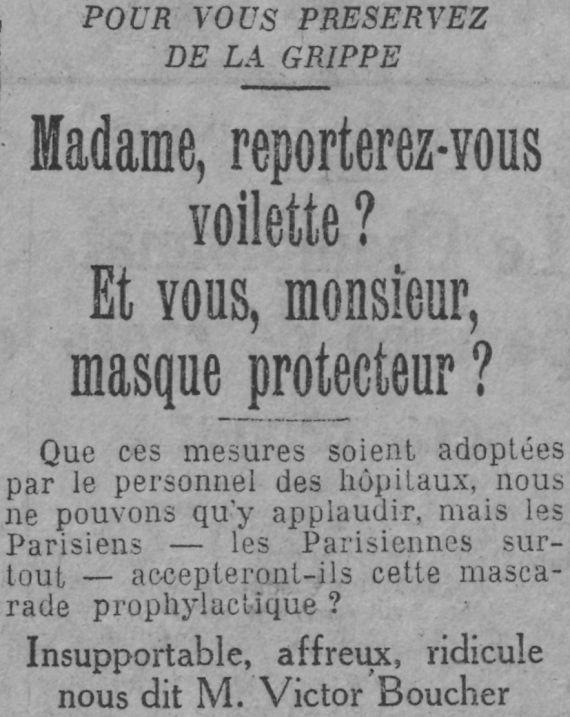

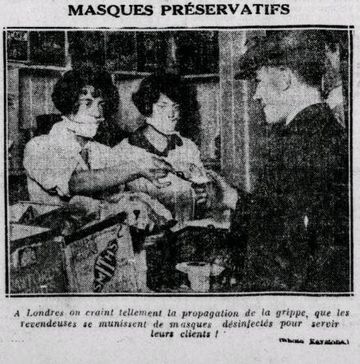

Despite the unambiguous recommendations of the Academy, the face mask, often scorned and ridiculed, has not been well accepted in France. Even though it was widely adopted by other countries during the pandemics of the 20th century, it struggled to find favour among the French, and the Parisians in particular, as this article, published during the second wave of the “Spanish” flu, makes clear:

“In England, the face mask was embraced to avoid contagion. Why is this not the case in France? Dr Netter, with his eminent practitioner’s perceptiveness, presented a practical mask three months ago. The Faculty adopted it, but not the public – a small section of public if truth be told, who, fearful of being ridiculed, prefer killing themselves by pneumococci and all the microbial agents projected by infected individuals when they cough or sneeze repeatedly in the tramways, buses and metros! In London, it is worn no questions asked, and in the busiest neighbourhoods, ladies, soldiers and solemn civilians can be seen protected by the mask – which does not prevent conversation – against the unfortunate and mysterious microbe.” (L’Heure, 26 February 1919)

In 1929, when the world was once again grappling with flu, Dr Henry Thierry, Chief Inspector of Technical Hygiene Services for Paris, defended wearing masks but remained little convinced of French citizens’ inclination in regards to this restrictive measure. He was nevertheless hopeful about the revival of a fashion item – the hat-veil – to convince the French to don protection against the viruses:

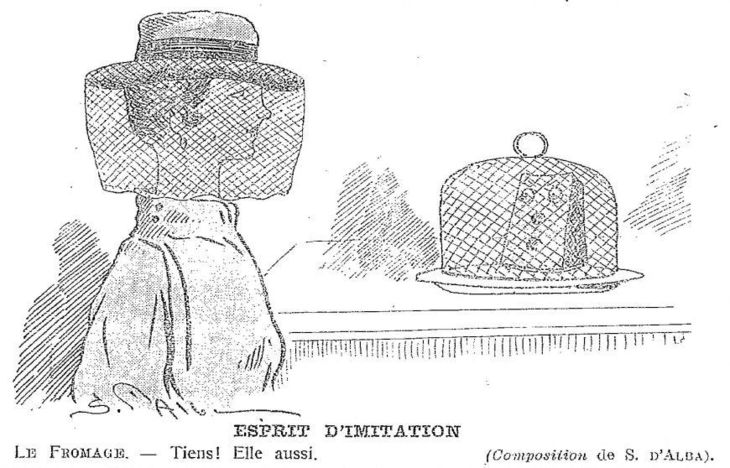

“French people do not take things seriously, even when in danger, and I am under no illusion that men in general will wear a mask, when, during the war, the officers had a hard time getting the soldiers to do so. But for women, among whom there was a clear predominance of deaths in 1918, which is still the case during this outbreak, it is so simple to protect oneself by bringing back a once fashionable accessory, the hat-veil, the success of which I do not doubt if a luxury fashion designer were to turn his attention to the problem and revive the trend”. (Le Matin, 3 March 1929, p. 2)

Two days later, a Paris-Soir survey, conducted among Parisian socialites, addressed the concerns and hopes of Dr Henry.

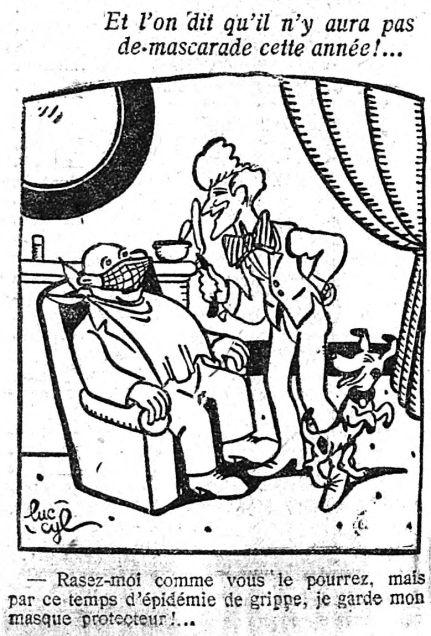

For the illustrator Poulbot, who did not believe that women would agree to "take up such an outdated fashion accessory again", wearing a hat-veil "had little chance of success", and this was confirmed by the actress Huguette Duflos when asked the question: "I think that hat-veils have long been relegated to the back of wardrobes along with the corset, wigs, hat pins and a few other old-fashioned accessories.” The actor Victor Boucher, also approached on the matter, was no more convinced by such measures: "I prefer to sneeze and blow my nose and sustain myself with drugs and herbal teas, for days, and even to stop appearing on the stage at La Michodière, than to wear a mask. It would be unbearable, awful and ridiculous. What’s more, it would never catch on and we might as well save ourselves the trouble. In France more than elsewhere, being ridiculed can be the end of someone. Better to die from flu if you have to."

Such was the outpouring of testimony and mockery as to the incompatibility of wearing a mask with Parisian fashion that the subject even became a well-worn cliché during outbreaks. The health issue thus moved from the medical sections to the trivial columns, while the mask itself continued to be cold-shouldered by the French.

"For a few days now, Londoners have been wearing masks against flu. And yesterday several newspapers published photographs showing them fairly disagreeably muzzled. But health matters above all else, does it not? Will our Parisian ladies follow the example set across the Channel? One would hope so, if not for us – deprived as we would be of the pleasure of contemplating their graceful faces – then at least for them. But the fact is, will the Parisian ladies agree to disfigure themselves to save their bronchial tubes? I fear they will prefer that these masks “flu” away instead… In fact, it would be like homeopathy!" ("Ça et là", Le Gaulois, 27 February 1919, p. 2)

In a tongue-in-cheek documentary in 1919, the L’Œuvre journalist, Marcel Coulaud, related his unsuccessful masked experience with one of his friends in the centre of the capital:

"I first of all noticed a certain astonishment. The Parisian crowd has had the unfortunate opportunity, during four years of war, of growing accustomed to seeing the most disparate faces, with the strangest customs...

— Look, two Tuaregs, murmured an educated little girl…

— No, no, my darling, the mother said. They are both disfigured...

I headed down to the Metro... And as happens to any traveller in a hurry to catch the departing train, the employee initially closed the gate in our faces.

Then, suddenly, overcome by compassion: — Oh, go on through, poor wretches, you’ve certainly earned it!

And the door opened before us.

In London, wearing masks has caught on quickly. This practical method of protecting oneself against the outbreak has swiftly been met with all-round approval. Paris is still behind the times. I made two signs aimed at rallying the Parisians to my cause.

“The Germans have been beaten, said one, but not the flu.”

"Put masks on, everyone... Try it and you’ll adopt it", I wrote on the other.

Then, donning these signs, like those men we used to see wearing sandwich boards, I walked up and down the boulevards...

I was met with respect ... and curiosity... but that was all.... My mask did not attract any positive approval...

— Is it possible to go out looking like that?

— These are people who fear the flu... Of course they didn’t stay in Paris at the time of the Berthas...

In the café where I settled myself, more than three hundred people surrounded me. Some behaved in a hostile manner.

And yet my faith in the face mask remains intact, and I hope that my example will not have been in vain for all that. In any case it will have served to earn me a seat in the Metro — what am I saying? Four seats — my neighbours hardly wishing to catch the flu from which they thought I suffered.

From 11 May 2020, with every other seat out of bounds on public transport, the French will have no other choice but to keep their distance and to adopt face masks, or face a stiff fine. The irony of history is worth pointing out here, though. A century later, when the French were finally ready to afford them a place in their wardrobe, the precious masks were no longer in sufficient supply! The history of face masks in France definitely seems destined to be written at the wrong time and is still steeped in uncertainty. Be that as it may, we now know that it will have to be adopted in public, which is not going to help matters where our cherished barbers are concerned…

Also worth reading:

Nejma Omari, "De la grippe espagnole au COVID-19 : ces remèdes qui promettent des miracles", Le Blog de Gallica.

Agnès Sandras, "L’humour face aux épidémies – Partie I à IV." in L'Histoire à la BnF, 09/04/2020.