By Nejma Omari, translated by Adriënne Ummels, University Paul-Valéry Montpellier

Did you know that until 2013 Parisian women were not legally allowed to wear pants in France? Indeed, the regulation established by the Paris Police Prefecture in 1800 prohibited women to wear the ‘masculine’ garment without a special authorization. This law was officially abolished merely five years ago. Pants – an absolute symbol of masculinity since the turn of the 18th to the 19th century – constitute the most important marker of gender in the Western World for the last two centuries. Although multiple works such as those by Christine Bard, Laurence Benaïm and Laure Murataddress the issue of women wearing pants through the emblematic characters and episodes of this struggle, an investigation of the digitized press between 1850 and 1945 renders the practices and phenomena of the daily life of French women who also participated in the normalization of this clothing item more visible. Fun facts, light-hearted chronicles and investigations included: the articles that we have consulted via the search engine of Gallica (developed by the National Library of France) and that of its commercial subsidiary Retronews allow us to confirm the role that the practice of sports, fashion, tourism and even work played during the process of the acceptance of women wearing pants. While this article proposes to discuss this subject matter by studying ordinary customs, a next blogpost will examine this question from an ideological and political angle.

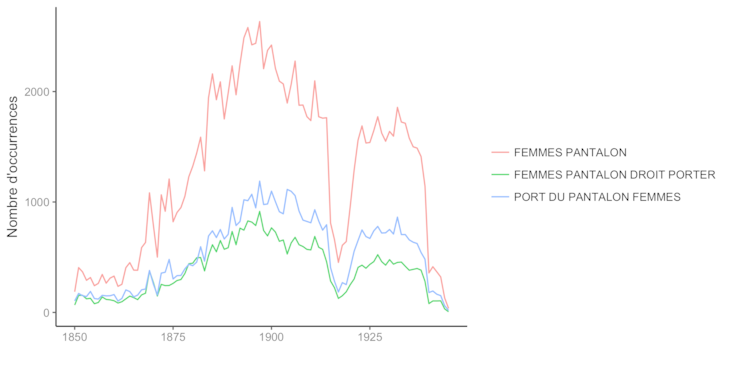

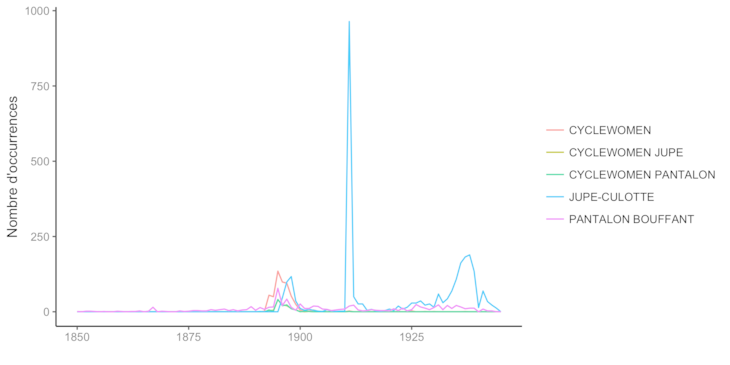

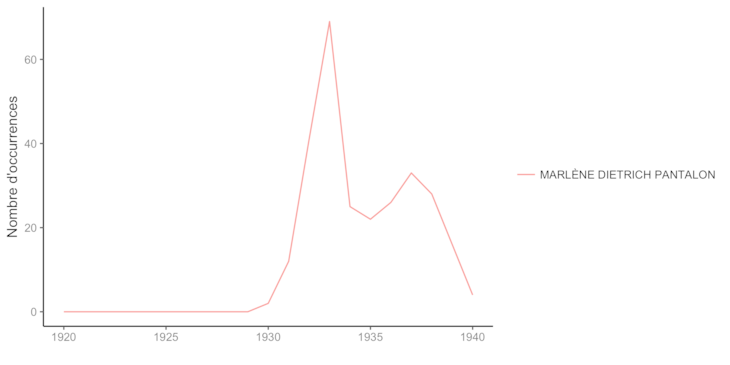

A first frequency analysis with the words “femmes” (“women”) and “pantalon” (“pants”) generates 123,522 occurrences on Retronews and 4,132 on Gallica. However, the search engine takes the entire page into account, which means that some of the results do not have anything to do with women wearing pants. Indeed, this tool does not allow us to confine the research to the cases where these words are nearby without being immediate “neighbours” (only research on exact expressions enables this, thanks to the use of quotation marks). Despite the margin of error, other analyses that include a more specific lexicon confirm the pivotal moments of the controversy. After a first peak during the Belle Époque, the debate encounters a second peak during the 1930s. In this blog we will examine some practices that marked these historical times.

Zouaves-women ride a bicycle

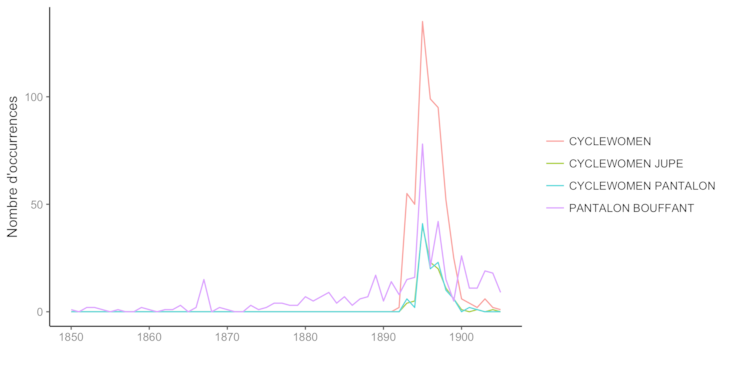

During the 1890s the bicycle, which was more accessible and comfortable, became a mode of transport that was much appreciated by French women. This female craze for the practice of cycling, which sparked a lot of controversy, explains the emergence of a specialized vocabulary as well as new dress codes. Amongst these specific terms, we can for example observe that, during the 1890s, the word “cyclewomen” emerges and is frequently used (see the following graph, the red curve). It is a false anglicism, a combination of the words “cycle” (“bicyclette”) and “women” (“femmes”).

The combination of this term with the words “pantalon” and then “jupe”, which produces similar results, reveals a problem. It is clear that the skirt was not suited for sport activities and tight pants could not be taken into consideration because of modesty reasons. Either way, some fashion columnists recommended wearing pants, but only under certain conditions:

Ladies, if you have a great body, do not fear pedalling while wearing pants. Otherwise... do not pedal at all... unless you don’t care what other people think. (Winnie, “Courrier de la mode et chronique feminine”, L’Univers Illustré, 19 October 1895)

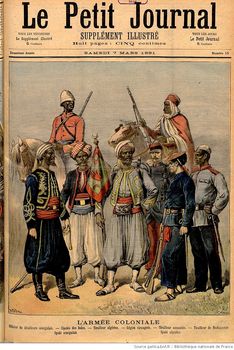

Finally, in 1895, the increasing passion of Parisians for the bicycle leds to the emergence of fashionable innovations, especially the idea of bloomers that recalled the uniform worn by the zouaves and Algerian skirmishers.

Suddenly inspired by the sweetness (in French “suavité”) of a cyclewoman wearing bloomers, a passerby with a Teutonic accent noticed this suavity with the following exclamation, truer than he thought: - Oh ! This suave woman ! (Schepers, n°206, Le Pêle-mêle, 7 March 1896)

There certainly exist [...] similarities between the zouave and the cyclewoman: both greatly harm the enemy. Only one of them shoots poisonous arrows from Cupid’s quiver, while the other one uses Lebel’s common bullet. (La Lanterne, 7 September 1895)

This extravagant garment, which gave female bikers a very particular appearance, revived the debate on women’s clothing. On 26 August 1895, Le Gaulois launched a “universal investigation” that aimed to respond to the following question: “which one of these two clothing items, the dress or pants, is better, in terms of beauty, hygiene and modesty”? Female personalities, in particular “those who the public already knew for their authority on art and their fine taste” presented their arguments: while Sarah Bernhardt spoke in favour of “the long dress”, Séverine deemed the cyclists’ “zou-zou pants” were “quite frankly ugly”. Bloomers were “brutal, often ridiculous” for Miss Brandès (26 August 1895), “grotesque” according to Mrs. Adam (27 August 1985) and “horrible” for Mrs Bréval” (1 September 1895). We cannot say that pants were unanimously endorsed...

The investigation, which is very instructive with regard to the public opinion of the time, is however difficult to find within the plethora of results that concern the search request “femmes et pantalon”. The tools developed by the NewsEye project would be able to prioritize this investigation, as well as the reaction of Police Commissioner Mr. Lépine, who decided to establish a draft decree in August 1895 (“Échos de Paris”, Le Gaulois, 11 August 1895, p. 1). Indeed, the commissioner noted an outbreak of cyclewomen wearing bloomers even though they did not own a bicycle. He thus wanted to forbid wearing pants outside cycling hours. Woe betide the cyclewomen who walk around as “widows of their machine”!

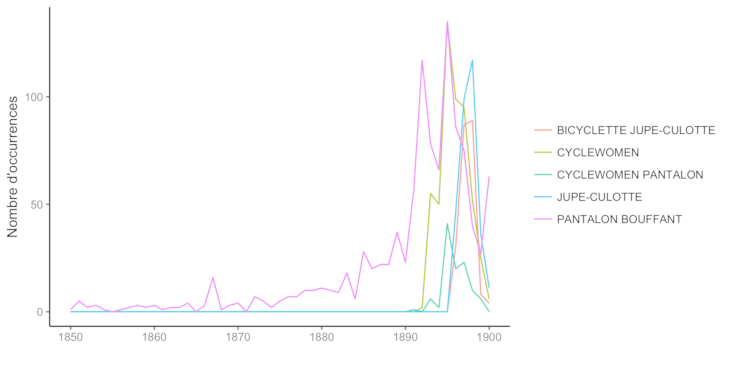

Even though the bloomers were unpleasant for some – especially for the “culottophobics” from Britain who found it “shocking to the last degree” and did not hesitate to boo the zouaves-women (Les Annales politiques et littéraires, 12 September 1897, p. 8) –, they did inspire a new item of clothing, halfway between skirt and pants: the “jupe-culotte”.

Although the jupe-culotte is often attributed to couturier Paul Poirier who popularised it in 1911, the clothing item was actually invented by Sandt and Laborde and patented under the name of “jupe-pantalon” by Henri Petit. The illustration of a female pedaller wearing a jupe-culotte went viral and circulated in multiple newspapers.

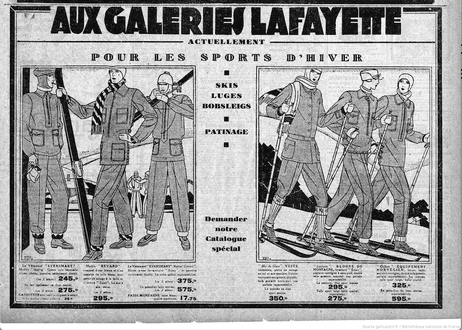

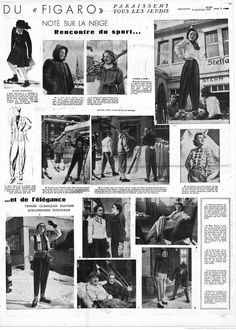

Eventually, like Francisque Sarcey declared in his column “Notes de la semaine” entitled “Jupon ou culotte”: “the bicycle, which renders wearing a culotte and a jacket almost necessary, only accelerated and sped up a modification of clothing, which would otherwise have gone slower and would have met more resistance” (Les Annales politiques et littéraires, 19 September 1897, p. 3.) Industrial innovations as well as the practice of sports (cycling is just one example) actively participated in the slow process of the acceptance of women’s pants. The jupe-culotte, which is quietly launched at the end of the 19th century, soared in popularity in the 20th century, just like the Norwegian pants and knickers that women wore for winter sports. The development of leisure activities and tourism also played a determining role, which the numerous illustrations on Gallica demonstrate.

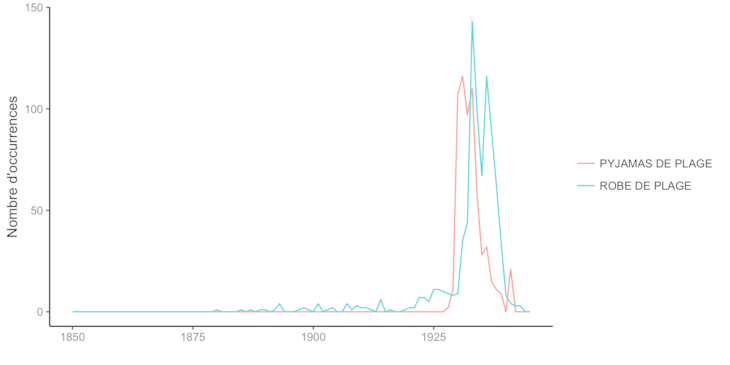

French women go to the beach wearing... pyjama trousers.

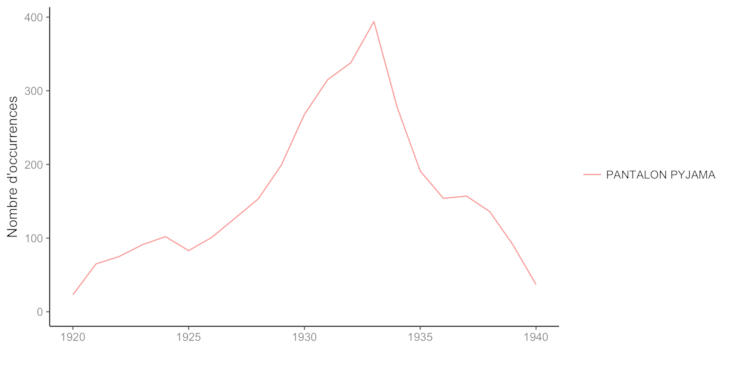

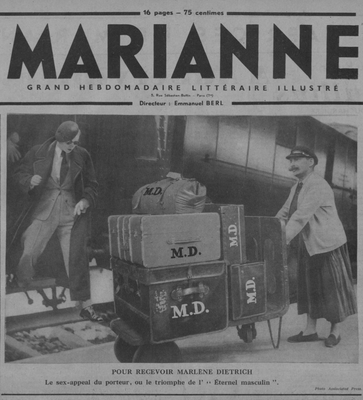

Women were not allowed to wear men’s clothing in public, but how about pyjama pants, a garment that is usually intended to be worn inside? A first frequency analysis with the terms “pantalon” (“pants”) and “pyjama” (“pyjamas”) shows a particular interest in the apparel during the mid-1930s. There is also a small peak in 1905, but this coincides with the representation of the one-act comedy play Le Pyjama by Jules Rateau. The year 1933 displays a record number of results that reunite the two words. This is also the year during which actress Marlène Dietrich legitimized pants in Hollywood by wearing a smoking. The boyish-looking celebrity exerted influence on a global scale and also affected women’s choice of night wear: “Pyjamas […] have regained topicality, thanks to the preference of Marlene and some other stars for the man’s suit” (Colette d’Avrily, Les Modes, 1st August 1993, p.18) It would be interesting for researchers to find these articles first and, more generally, those concerning major figures that inspired women’s daily life.

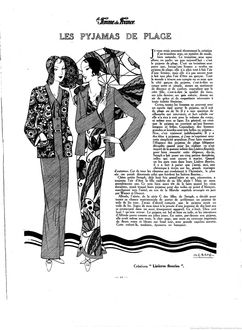

Even before the Hollywood actress, however, it was the famous fashion designer Coco Chanel who popularized pyjamas and suggested that they could be worn on the beach or during summer evenings. So far from the comfortable night garment, these elegant “beach pyjamas” were a hit and won French women’s hearts. Some of them payed a lot of money for this summer must-have: another reason to look after your suitcase!

Someone stole... Dresses and beach pyjamas. Miss Marcelle Peltier, who lives in Paris at 117 boulevard Masséna, reported the theft of her suitcase by an unknown person. It was filled with dresses and beach pyjamas with an estimated value of 4,000 franks, and was stolen when she made a stop in a café on avenue Janvier. (L’Ouest-Éclair, Rennes, 14 August 1939, p. 7)

The success of this new garment is also related to the fact that it was presented as a compromise between women’s clothing and a more masculine outfit, a sort of third sex meant to please everybody:

I recently announced the creation of a third sex, with regard to fashion, that is. Today, we are going to talk about this third sex for a bit: the beach pyjamas. It is a third sex because, when a woman is wearing beach pyjamas, she does not really looks like a woman, but she doesn’t look like a boy either. There is something for everybody in the sense that the boyish side, that is the neat and simple cut, assures a feeling of decency and comfort, while the girlish side, that is the quality of the fabric, its beautiful prints, its bright colours, create a gracious look that is a necessity for every woman’s outfit. (Séraph, “Les Pyjamas de plage”, La Femme en France, 29 June 1930, p. 13)

In spite of this femininity, some women preferred a pretty beach dress or even “pyjamas-skirts”, an invention from 1933 that gave women a gracious allure. Finally, the battle between the skirt and pants took place at the beach, from Deauville to Biarritz, with the rivalry of pyjamas and the dress: “It will be a tense fight. Who will win once again? The dress or pyjamas?” (Gisèle de Biezville, “Robes de plages ou de pyjamas”, L’Intransigeant, 24 May 1933, p. 8). A frequency analysis on Retronews is only available per year, so we cannot create a graph that shows the number of occurrences per month. This function would allow us to note that the thematic pyjamas-dress is a recurring topic that, during the 1930s, repeated itself every year before summer.

If these questions seem frivolous, they helped masculine pants, in different forms, to enter women’s wardrobes. Numerous events, such as competitions for the most beautiful “beach pyjamas” or fashion shows, proposed to highlight women wearing pants without it being an act of transgression or a feminist claim.

Every now and then demonstrations took place as well, such as the “day of the dungarees”, which was organised by Comœdia in order to fight against the price increase of clothing and which united men, women “and even dogs” (clarified by Le Petit Journal, 20 April 1920). They were all dressed in the same masculine clothing: “after having defeated the external enemy wearing the sky-blue uniform, we will defeat the internal enemy, that is the increase, with our blue dungarees. This perspective allows us to see the world through rose-tinted glasses.” It is important to note that this is not the first time that women put on dungarees, because many women took on men’s jobs during the Great War.

Although opponents decried pants, eventually even they had to admit that the garment had numerous advantages: pants were practical, comfortable and closed. They allowed women to practice sports, to work or even to travel without violating their modesty.

Who knows whether in fifty years, honest women (for whom this is the only way that they can go out in the street without being insulted by boors) will all dress as men, a more comfortable outfit than dresses that also enables them to equip themselves with a defence cane or revolver to come back home at seven o’clock at night? This is possible, after all. Men traded the dress for pants, and they are pretty happy about it. Who tells you that women will not follow this example? (A. Paulon, “À propos de l’affaire Montifaud-Magnard-Camescasse”, Le Tintamarre, 24 September 1882)

Almost 140 years later, we must conclude that Mr. Paulon’s projection was false: how often do you run into women on the street that are equipped with a self-defence cane or a revolver…?

Nejma Omari, translated by Adriënne Ummels