NewsEyen blogia kirjoittavat tiimimme jäsenet. Blogissa tuodaan terveisiä konferensseista, pohdiskellaan ajankohtaisia asioita, kerrotaan projektin sisäisiä uutisia sekä esitellään tiivistä tietoa tapaustutkimuksistamme tai projektiin liittyvistä julkaisuista. Blogikirjoitukset ovat pääosin englanninkielisiä, mutta voivat silloin tällöin sisältää muutakin kirjoittajan suosimaa kieltä – olemmehan monikielinen joukko! Mukavia lukuhetkiä!

The invention of Mother’s Day: origins, media history and gift ideas

This year, Mother's Day will take place on the 30th of May in France, weeks after other countries such as Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany and the United Kingdom. What makes French Mother's Day special? Read more to find out!

This post is available in its original French version on Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/05062020/linvention-de-la-fete-des-meres-origines-histoire-mediatique-et-idees-cadeaux

A commercial initiative developed by a consortium of avaricious florists? A product of the Vichy regime? Or maybe a strategy of the pasta necklaces lobby? Where did Mother’s Day really come from and what is its history? Let’s investigate.

Even though Mother’s Day as we know it today was passed down to us from the late 19th century, the first celebrations of motherhood can actually be traced all the way back to Antiquity, with the festivities organised in honour of the Greek goddess-mothers Gaia and Rhea and then the Matronalia ceremonies in Rome. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Marian devotion paid tribute to the Mother of Christ, who symbolised purity and the maternal ideal and, through her, all women whose most important vocation was to have children.

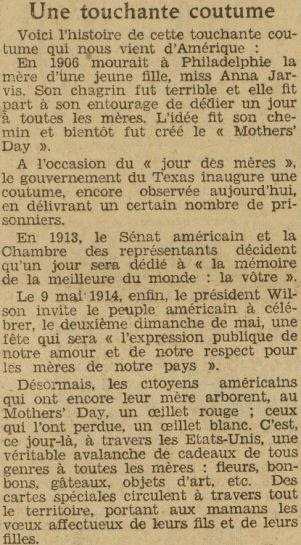

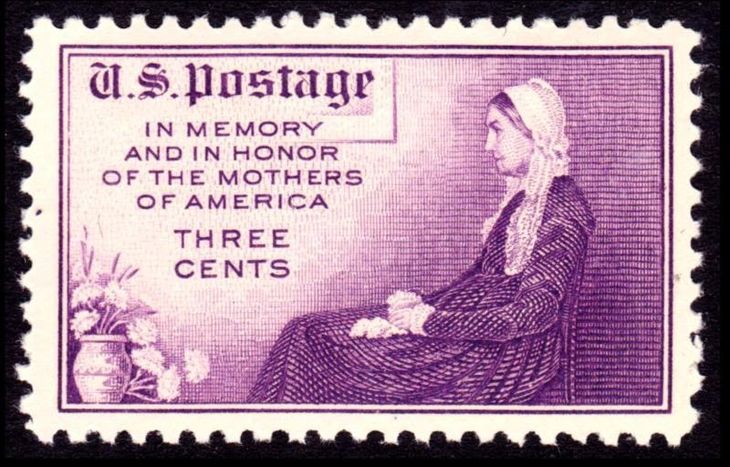

From the end of the 15th century, Mothering Sunday was celebrated by Christians in what are now the UK and Ireland on the fourth Sunday of Lent. It particularly gave servants a day’s leave to go to the "mother" church and visit their families. Daughters offered a simnel cake to their mothers to mark the occasion, decorated with 11 marzipan balls (symbolising the apostles, minus Judas), and this is still traditionally eaten at Easter in the English-speaking world today. This religious celebration gradually went out of fashion throughout the 19th century, however, and was replaced by the American Mother’s Day, created by Anna Jarvis at the turn of the 20th century. When her mother died in 1905, Anna Jarvis, a teacher and pacifist activist, devoted herself to officially establishing the celebration of motherhood as her deceased mother had wished. So began a seven-year campaign which eventually culminated in the US Government’s creation, in 1914, of a holiday reserved for mothers on the second Sunday in May.

US post office stamp / in the public domain

Much to the great despair of its creator, however, Mother’s Day soon gained in commercial appeal and lost its religious significance as it spread around the world: the UK, Germany, Belgium, Finland and Turkey all embraced it in turn during the first half of the 20th century. It was celebrated at different times of the year depending on the country.

But how did this festival gain currency in France? And what role did the press play in sustaining this tradition?

A birthrate stimulator: "Mother's Day for large families"

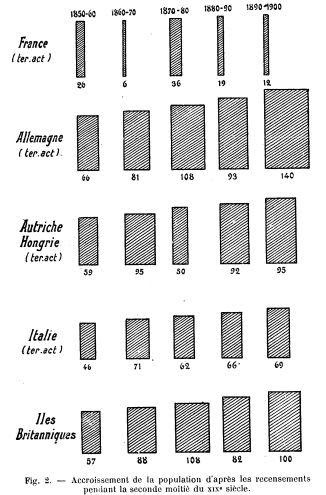

Under the Napoleonic Code (French Civil Code) of 1804, women were subject to marital authority; regarded as minors in the eyes of the law, they were reduced to childbearing and educating roles, even though they had no ultimate say over their children. With a view of firmly entrenching this family model and paying homage to his own mother, the Emperor hoped to introduce a national festival in the spring, but his idea never materialised. It was not until the Third Republic that these plans returned to the agenda. France’s slowing demographics during the latter half of the 19th century and the organisation of the neo-Malthusian movement caused concern among populationist associations, whose members campaigned to stop the declining birth rates and bring them back to the level of their European neighbours, particularly Germany.

According to Jacques Bertillon, the statistician and demographer behind the foundation of the "National Alliance for Increasing France’s Population", in 1896 the falling birth rates were undermining France’s wider influence, the French language and even the development of agriculture and industry. In his pro-birth propaganda publications, he updated and analysed the causes of depopulation before outlining "remedies against the scourge”. Among the various measures mentioned – bonuses for the birth of the third child, jobs reserved for large families, family benefits and support for widows with more than three young children – Bertillon suggested the annual celebration across all French towns and cities of a "children’s festival" in tribute to large families:

“In France, these sorts of festivals are not unknown. They should be promoted everywhere, like in the Netherlands. […] They [large families] should not be summoned merely to be handed a few silver coins across the counter. No, they should be rewarded publicly in a fitting formal occasion." Depopulation in France, p. 288

Émile Zola, who was a member of the Alliance for Increasing France’s Population, made French mothers the cornerstone of the pro-birth strategy in a front-page article supporting his cause, published in the Figaro’s 23 May 1896 edition, and then in his novel Fecundity, the first volume of the "The Four Gospels" series:

"Oh French mothers, bear children so that France retains its rank, its strength and its prosperity, for it is necessary for the world’s salvation that France should live, for from her came human emancipation, and from her will come all truth and all justice!" "Depopulation", 23 May 1896, Figaro

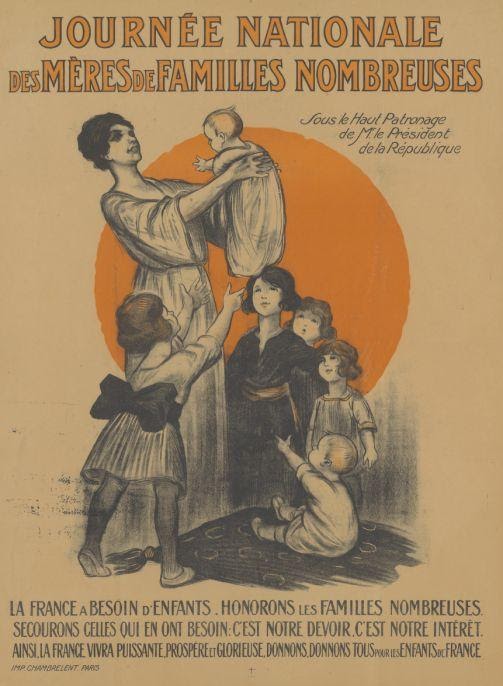

The children’s festival suggested by Jacques Bertillon would thus make way for a "Mothers of Large Families Day" at the turn of the 20th century, particularly thanks to the efforts of a pro-family group from the Isère département, "the fellowship of worthy fathers from Artas", set up in 1904. The big community event organised in Artas on 10 June 1906 in honour of "worthy mothers" is considered to be the first such celebration on a large scale, but it actually followed a series of local initiatives held from the second half of the 19th century across various regions in France.

Whilst they heralded the beginning of the tradition, “Mothers of Large Families’ Day” struggled to catch on in France, and it was not until World War I, inspired by the Mother’s Day celebrations made by American soldiers, that this special celebration for mothers became a permanent addition to the calendar of French holidays.

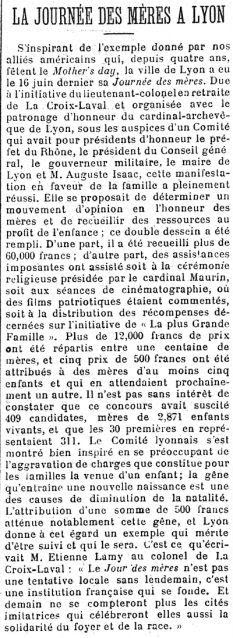

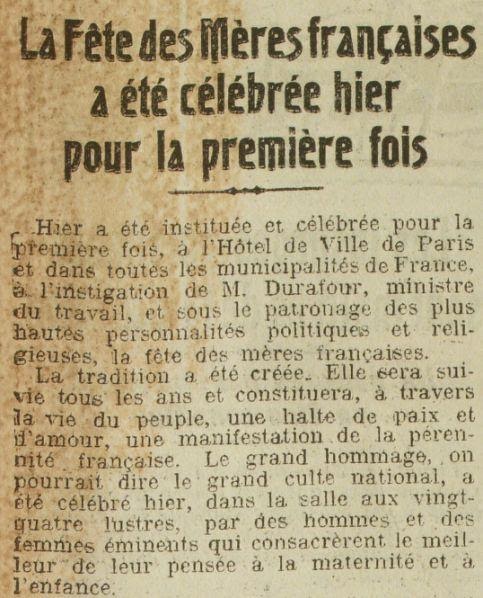

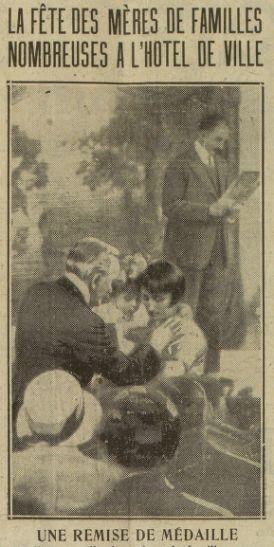

In the wake of the successful Mother’s Day organised in Lyon in 1918, which garnered extensive media coverage, an array of similar events emerged nationwide, complete with contests, film screenings, awarding of medals and even ceremonies at the tomb of the unknown soldier. The “large family” criterion may have been dropped from the festival’s title in 1926 when it became an official event, but amid continuing pro-birth propaganda, the press continued to champion mothers with more than three children in the 1930s.

"Labour, Family, Homeland"

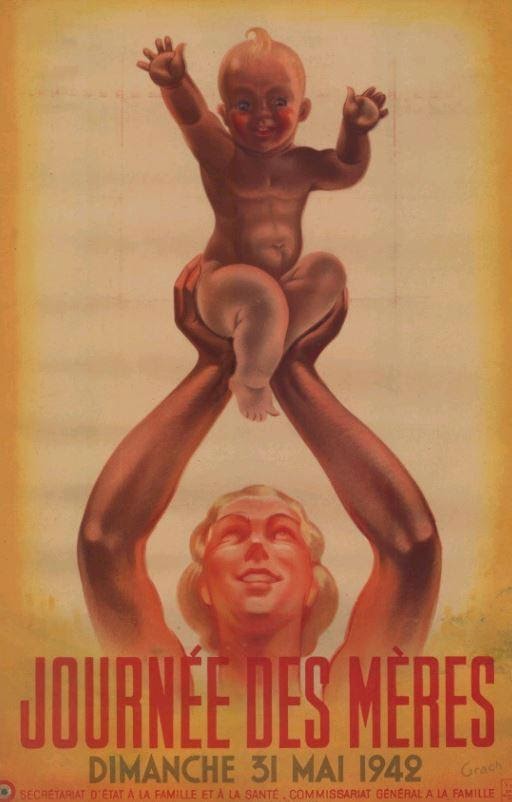

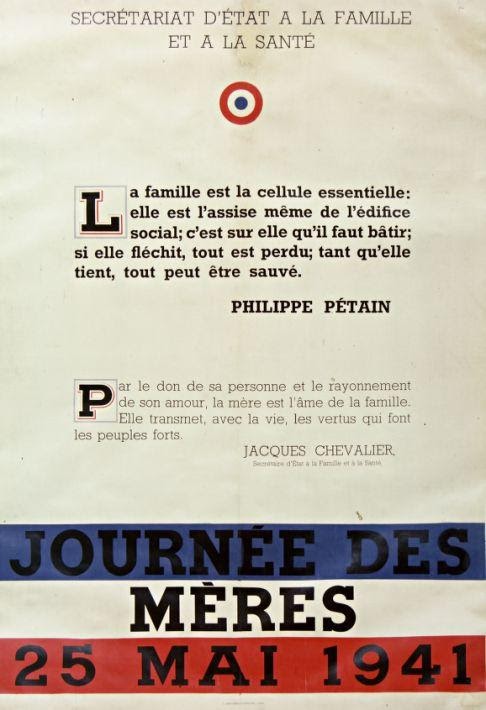

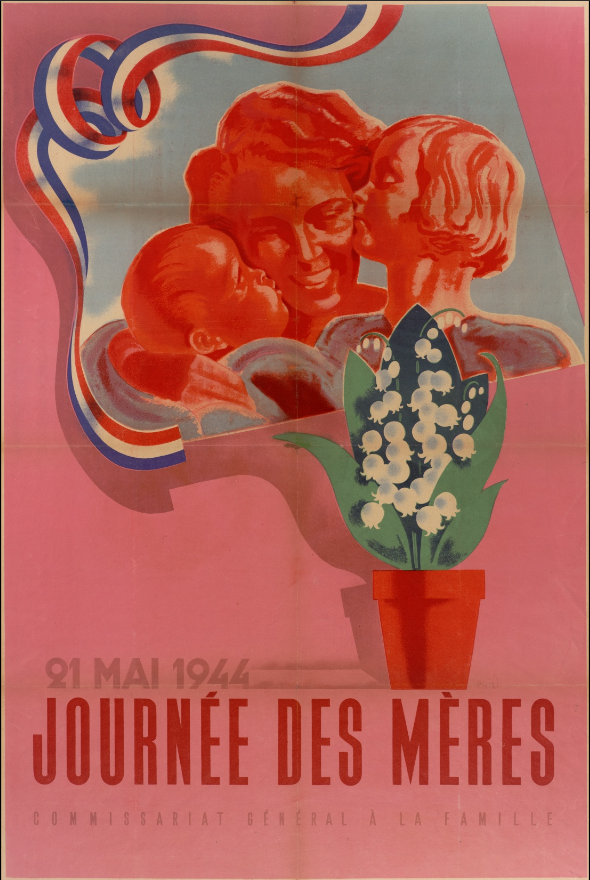

Contrary to the commonly held beliefs around the origins of this tradition, it was not Pétain, therefore, who invented Mother’s Day. That said, it was indeed the Marshal who made the festival part of the political calendar from 25 May 1941, turning it into “an ideological slogan to serve the homeland” as the historian Louis-Pascal Jacquemond explained in his recent publication. The myriad of leaflets and posters distributed in those days illustrated the Vichy regime’s efforts to promote the family values embodied by mothers and to uphold the pro-family movement. These flyers were handed out to schoolchildren and teachers in tandem with the festival’s inclusion in school curricula, encouraging children to make small gifts for their beloved mothers. But beyond the traditional drawings and poems, what other things could children back then give their mothers?

"Moulinex liberates women!"

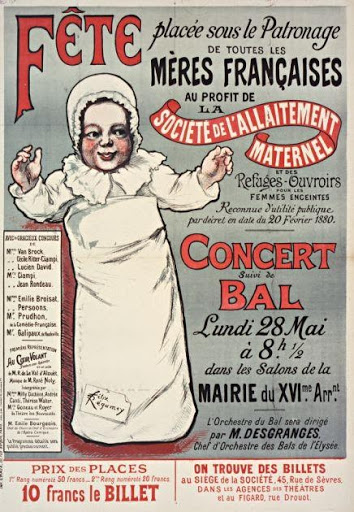

In the early 20th century, until the 1950s and ‘60s, bouquets of flowers were the first gifts to be widely promoted by posters. Offering cut flowers, succulent plants or flower bushes, together with a greeting card, thus became the custom on this special occasion.

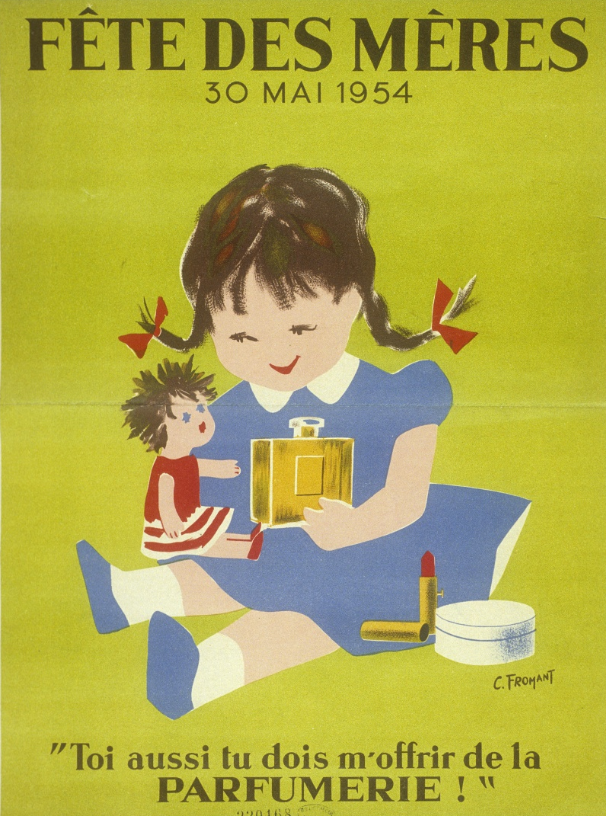

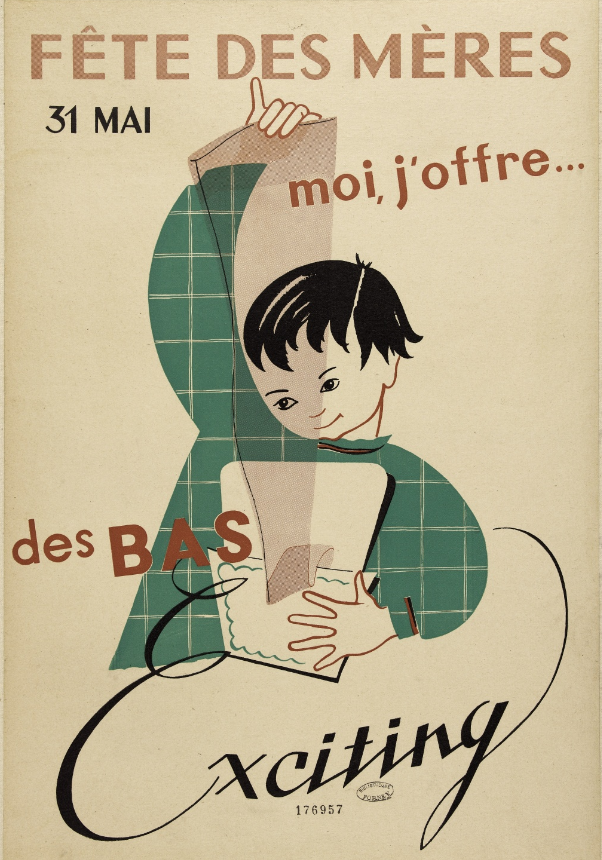

It was not until after World War II, during the thirty-year post-war boom when a consumer society began to take shape, that adverts proliferated for cosmetics brands, perfume, lingerie, kitchen utensils and other household appliances. By attributing the household chores to women, these adverts reinforced the stereotypical perception of the housewife. The advertising slogan registered by the company Moulinex, "Moulinex liberates women!", should not therefore be construed as a promise of sexual empowerment and a rallying cry for the status of women in society, but as a time-saving pledge, allowing women to devote themselves to their husband as well as run the family home.

Whilst these gendered adverts might strike us as preposterous today, there is still a long way to go in the advertising industry, as demonstrated by the French neologism publisexisme, which refers to the eroticisation of the female body for advertising purposes. With such reification of women perpetuating male domination, along with new family structures emerging (such as single parenting, assisted human reproduction, homosexual marriage and blended families), how relevant is it to continue celebrating a festival based on an archaic and obsolete model? The future of Mother’s Day, therefore, looks far from certain, and that’s why we cannot encourage you enough this Sunday to come up with some innovative ideas for spoiling your special mum with a flower necklace or a pasta bouquet (whether you're in France or not)!

Also worth reading:

- Louis-Pascal Jacquemond, Histoire de la fête des Mères. Non, Pétain ne l’a pas inventée !, préface de Françoise Thébaud, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2019

- Pierre Ancery, "Comment élever ses enfants", selon Vichy, RetroNews