Unsere Blogartikel werden von Mitgliedern des Projektteams verfasst. Die Themen umfassen ein breites Spektrum: Bericht über Tagungen, auf denen wir vertreten waren, Reflexionen über aktuelle Herausforderungen und Themen, interne Ergebnisse und Fortschrittsberichte, Case Studies aus dem Bereich der digitalen Geisteswissenschaften, sowie Nachrichten über aktuelle Publikationen aus dem Projekt. Die Blogbeiträge werden hauptsächlich auf Englisch verfasst, ab und zu aber auch in der Sprache des*der Verfasser*in. Wir sind schließlich ein multilinguales Team! Wir wünschen spannende Lektüre.

From the Spanish flu to Covid-19: the remedies claiming to work miracles

This post is available is its original French version on Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/06052020/de-la-grippe-espagnole-au-covid-19-ces-remedes-qui-promettent-des-miracles

At the height of the Covid-19 health crisis, the media is awash with a wave of alleged miracle cures, including disinfectant injections, UV, fennel and plant-based magic potions... A not dissimilar situation to a hundred years ago, during the so-called “Spanish” flu.

Ever since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the web has been rife with fake news as to where the virus came from, how it is spread and treatments for it. To tackle this fast-spreading misinformation, on its website the World Health Organization (WHO) has had to list and refute the most far-fetched rumours, especially those touting pseudo-miracle cures. Among the myth-busters it has put online are: "FACT: Drinking alcohol does not protect you against Covid-19 and can be dangerous", "There is no evidence from the current outbreak that eating garlic has protected people from the new coronavirus", "Taking a hot bath does not prevent the new coronavirus disease […] Actually, taking a hot bath with extremely hot water can be harmful, as it can burn you" and "No. Sesame oil does not kill the new coronavirus." And the WHO concludes: "To date, there is no specific medicine recommended to prevent or treat the new coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Such myths are tenacious though, and they are still going strong on social media, in the press and even in the rhetoric of political leaders. But they are not only the product of our era. Searches in the digitised 20th century press collection of the digital library Gallica bring up a great many articles dated from the time of the flu pandemic that wrought global havoc between 1918 and 1920. These extolled the virtues of promising medicines, old-fashioned remedies and therapeutic cures believed to be able to overcome the disease. And what is striking about these treatments, peddled by the 20th century press, is that they look a lot like the therapies that are considered to be beneficial by the media today!

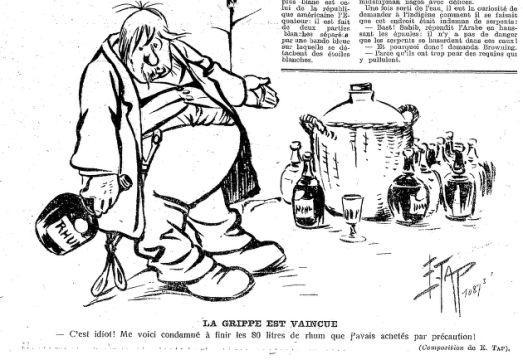

Rum to counter the flu

Right from the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, social media has been bombarded with all manners of dubious posts trumpeting the effectiveness of alcohol (vodka especially) against the virus; while some recommend using it to disinfect surfaces or concoct a home-made alcohol-based hand sanitiser, others advise quite simply drinking it to protect against the disease. Such hypotheses about the prophylactic and curative properties of alcohol are not new. In 1918, amid a second wave sweeping across France, rum was recommended to combat the septic enemy. Officially recognised by doctors as a prevention and treatment remedy, rum was even distributed by the Ministry of Supplies. On 29 October 1918, a press release announced the sale of 500 hectolitres of rum to the City of Paris to help it curb the spread of flu ("Rum: a flu remedy", Le Petit Parisien, 29 October 1918, p. 2 ). But speculation abounded about this sovereign beverage and its price went through the roof:

"It would appear that the big producers of rum from the French islands had planned, ahead of the flu epidemic, for the day when sugar production would sit on the back burner as they poured all of their energy into alcohol production. Rum is now ranked among the top brand liqueurs and is consequently selling at exorbitant prices since the medical profession has been prescribing it as an excellent buffer from or remedy for flu. It is not uncommon for a litre of rum to cost twenty or twenty-five francs even at the local grocer. […] We wonder if such shameless speculation around what you could say was a pharmaceutical product should be tolerated" (P.D, "There’s some rum… but for what price!", Le Radical, 31 October 1918, p. 2).

From soaring rum prices to the rush for alcohol-based hand sanitiser or masks, every epidemic seems to have its lot of speculators...! Watch out for reprisals, however:

"The fraud department has opened an investigation into certain schemes that have driven the hike in rum prices at a time when this product was particularly sought-after as a flu remedy. Middlemen having never seen a bottle of rum pass through their hands have reaped profits of 400 francs per hectolitre; retailers have earned as much as 70 0/0. A raft of reports has been submitted to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and legal proceedings have been initiated against the speculators. All of the offenders will be brought before the courts" ("News in brief. Speculation around rum", Le Temps, 20 December 1918, p. 3).

Garlic and onion

Over the past few months, who among us hasn’t received, via an instant chat app, at least one pontificating message unveiling the recipe for a new magic cocktail to protect against Covid-19? Whether made of plants, bicarbonate of soda, hot water, lemon juice or fennel, all sorts of brews are recommended for boosting our immune system and making it “coronavirus-proof”. Among the most popular of these miracle potions on social media is herbal tea made from garlic, for its antimicrobial properties alleged to protect against the virus. Back during the Spanish flu, another bulb received expansive newspaper coverage:

"Amid this malignant flu epidemic, here’s a time-honoured folk remedy that an officer acquaintance of our friends has recommended to us: There is an old remedy, as surprising in its effects as it is simple: the onion. A military doctor, who combines modesty with the most tried-and-tested science, treats flu patients at the hospital he runs by giving them, from the first signs of the illness, a daily dose of 200 cubic centimetres of crushed onion juice, taken three times in hot tea. This brings down high temperatures in two days. None of the more than 80 patients treated in this way has died. Only one, having refused the brew, contracted bronchopneumonia; but this did not persist longer than six days with the medicine being administered as a wash. Alongside the medication, mustard plasters are applied to the upper chest. The above findings seem to be conclusive enough to merit attention from the public, the medical profession and even the authorities" ("The Flu. An old-fashioned remedy", L’Écho d’Alger, 15 November 1918, p. 3).

The "headlines" in the 21 November 1918 issue of La Lanterne also announced the success story of a doctor from Boulogne-sur-Mer who apparently obtained "encouraging results" by treating the flu with onion juice. As is often the case when it comes to backing up health-related claims, the articles feature testimonies from alleged medical authorities in a bid to substantiate the remedies lauded. “Doctors” also wield a rhetorical power, as demonstrated by the phenomenal rise in fennel sales last February in Cape Verde, after a rumour went viral that a "Brazilian infectious diseases specialist” had recommended drinking fennel tea twice a day to ward off the virus.

Heat

Apart from consuming an array of different beverages, there are other theories circulating about the effectiveness of ultraviolet rays on the epidemic. The possibility that transmission of the virus could slow over the summer, as happens with seasonal influenza, has sparked widespread speculation. If heat is effective against Covid, why not just increase our body temperature and combine the beneficial with the enjoyable by lounging in a soothing and immunising hot bath? In February 1919, the virtues of heat against the flu, and sweating in particular, were also extolled after tests by a Swedish doctor:

"Stockholm, 9 February – Dr Bjœrson is releasing a statement about a new procedure for curing the Spanish flu. The treatment involves exposing patients’ backs to a powerful device emitting heat and electric light which causes intense sweating. All of the patients undergoing this treatment were cured within two to five days" ("Sweating as a flu remedy", La Petite Gironde, 10 February 1919, p. 1).

La Baïonnette, 6 February 1919

Advertisements for heated pharmaceutical products were also common, such as for "beneficial heated cotton" which, when "applied to the chest emits first a strong heat and then a gentle heat over a long period" and can thus cure flu patients. All that for the modest sum of 2 francs 50…! More generally, on the fourth page of the newspaper, usually set aside for adverts, is a whole spread of so-called miracle therapies. These include "Dianoux Tar", "Pink pills" or “grippecure”, literally the "flu-cure", promising recovery in record time. Where some of these medicines existed before the 1918 flu, the adverts are updated to include a paragraph on the Spanish flu:

"Taking a dose of 2 grippecure pills before each meal is enough to swiftly heal – sometimes even in just one day – the most tenacious flu, however severe it may be, and the most persistent flu. […] NB – During the current Spanish flu epidemic, we cannot recommend taking GRIPPECURE enough. This is an excellent remedy for curing the ailment as soon as it appears, and even for preventing it" (“Root out the ill”, Le Matin, p. 4).

Advertisements above: "The oak tree and the reed", Le Petit Parisien, 26 February 1919 / "The sword of Damocles", Le Matin, 1 December 1918 / "Root out the ill", Le Matin, 4 January 1919 / "Don’t underestimate it", Le Petit Parisien, 12 December 1918

Such tactics, which would be condemned by the General Directorate for Competition, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control (DGCCRF) today, were not uncommon in the 20th century. Accordingly, brands readily disguised their advertisements as short stories or personal accounts beside which they printed medallion portraits in an effort to lend more credibility to their claims:

"A moral on its own is boring; a story weaves the precept into it. So here is our short story which takes place in the Lude (in the Sarthe), where Ms Eseverri lives on Church square. The debilitating Spanish flu – or the old influenza if you prefer, for although its name has changed, the adverse symptoms have remained – has taken its toll on Ms Eseverri as it has on pretty much everyone. Ms Eseverri had eventually recovered from the illness, but she could not shake off what we have agreed to call the after-effects of the flu: "I eventually got over the flu, she writes, but even though I no longer had any acute symptoms, this illness had left me with lasting effects. Despite the treatments, I didn’t feel my strength return, I remained pale, with no drive, always sullen and glum. […] In our newspaper Le Petit Parisien, I had always read the recovery testimonies involving Pink Pills that it published […] The Pink Pills didn’t let me down. Thanks to them, I am back to being as fit as a fiddle. An anaemic friend, seeing the wonderful effects they had had on me, also took your pills and felt better because of it. My husband himself, when he feels tired, takes a few Pink Pills and perks right back up again". Our story ends with Ms Eseverri’s recovery. The precept is this: "When you’re facing illness, Pink Pills will face it with you" (Le Gaulois, 26 March 1919, p. 3).

Be careful not to confuse advertisements and fake news with satirical and humoristic articles, however, which ridicule misleading recommendations and scoff at human behaviour. Here are a few examples:

"The Spanish flu. — A Mexican scientist, Pedro Barranza, has just discovered the remedy for the Spanish flu. Since this illness is generally caused by contamination of the nose and mouth, during the crisis, all one has to do is sew one’s lips together with thick thread and plug one’s nose with simple glazier’s mastic. Since the microbe can’t get in, the illness will be avoided" ("Gossip column", Le Régiment, 23 January 1919, p. 9).

"The doctors advise gargling with oxygenated water: oxygenated water can’t be found anywhere. Anywhere? That’s debatable: the other day, I saw a lady at the hairdresser’s getting her hair coloured blonde with oxygenated water. And she’s not the only one. If all of the oxygenated water hoarded by hairdressers was requisitioned, there would be plenty to supply pharmacies and save people from the dreaded flu. But no, these ladies want to look blonde. Go into the music-hall where the four-hundred prettiest women in Paris can be found. Count how many have oxygenated hair, the litres spread on the dainty heads of these ladies that would go to much better use in the throats of patients to destroy the bad germs. Will no one make the women see reason, do a kind deed – a patriotic deed I might even say? Could the reign of oxygenated women not come to an end this grim autumn of 1918? It’s not even very attractive, a woman with coloured hair or bleached hair. That’s our opinion" ("Around the flu", L’Œuvre, 25 October 1918, p. 3).

It would seem that, a century later, the wishes of the L’Œuvre journalist have been heard: with hairdressers closed until 11 May, few women have been able to pride themselves on still having nicely coloured or bleached hair today! In the end, the most effective prevention in these difficult times seems to be, when it’s possible, to stay at home, which can avoid a whole host of disappointments…

Also worth reading:

"La grippe espagnole", article published on the Gallica blog in 2018.[Textflussumbruch]Agnès Sandras, "L’humour face aux épidémies – Partie I à IV." in L'Histoire à la BnF, 09/04/2020.

To find out more:

Roy Pinker, Fake news et viralité avant internet. Les lapins du Père-Lachaise et autres légendes médiatiques, Paris, CNRS éditions, June 2020.[Textflussumbruch]The pandemic special theme section (“spécial pandémie”) on the "Actualité du XIXe siècle" platform.