Les articles du blog NewsEye sont rédigés par les membres de notre équipe projet. Parmi les thèmes traités figurent les conférences auxquelles nous assistons, des réflexions sur les questions d’actualité pertinentes, des actualités et les avancés de notre projet, ainsi que du contenu plus succinct diffusé dans le cadre de nos études de cas sur les humanités numériques ou de nos publications relatives au projet. Les articles du blog sont publiés principalement en anglais, mais néanmoins proposés de temps à autre dans la langue de prédilection du membre de l’équipe projet concerné, puisque notre petite troupe parle plusieurs langues ! Bonne lecture !

Building a Bilingual Nation

Hufvudstadsbladet. Helsingin Sanomat. Åbo Underrättelser. Do you know which one of these is a Finnish newspaper? Actually, all of them are. Helsingin Sanomat is published in Helsinki, our capital city, and so is Hufvudstadsbladet. Finland is a bilingual country, which is why we have Helsingin Sanomat in Finnish and Hufvudstadsbladet in Swedish. Åbo Underrättelser is a Swedish-language newspaper published in Turku (Åbo in Swedish), our former capital and the place where our first newspapers were born in the late 18th and early 19th century.

The above-mentioned newspapers are part of the NewsEye corpus provided by the National Library of Finland. Several titles from the two towns and in two languages were selected, taking into consideration the significance and history of the titles. All volumes of these digitized newspapers up to 1918 are included in the corpora.

There was a lot going on in Finland in the 19th century: growth of the press, nation-building, and a language battle in which Fennomans fought for the rights of the Finnish language and Svecomans defended the Swedish language. Swedish was spoken in the coastal areas, whereas Finnish was spoken inland. Swedish was the language of administration and educated people, because Finland had been part of Sweden for centuries. Between 1809 and 1917, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia, and at this time the censorship laws of 1829 and 1850 had an impact on the press.

Let’s have a closer look at the Finnish NewsEye titles.

Åbo Underrättelser (ÅU) is the oldest Finnish newspaper which is still published today. It was founded in Turku in 1824 to succeed Mnemosyne (which was founded five years earlier). In its early day, ÅU focused on literary and academic matters. Turku was the largest city in Finland then as well as home to the first Finnish university. After the great fire of Turku in 1827, the university was relocated in Helsinki and Turku was no longer the center of academic life in Finland. ÅU changed its focus and was now targeted on merchants and families.

As of the late 1830s, there was strong competition between the two Swedish-language newspapers in Turku, Åbo Underrättelser and Åbo Tidningar. ÅU had a liberal profile and very skillful journalists and it managed to gain larger circulation than the conservative Åbo Tidningar.

ÅU called for constitutional rights for Finland in the 1860s and encountered difficulties with censorship. When its editor lost his right of publication, the newspaper was relaunched with a new editor and a slightly modified title.

Later, ÅU started to support the Svecoman movement and its content came closer to that of Åbo Tidning (another Turku newspaper). In 1907 these two papers were merged. The new company continued publishing ÅU every day and Västra Finland twice a week.

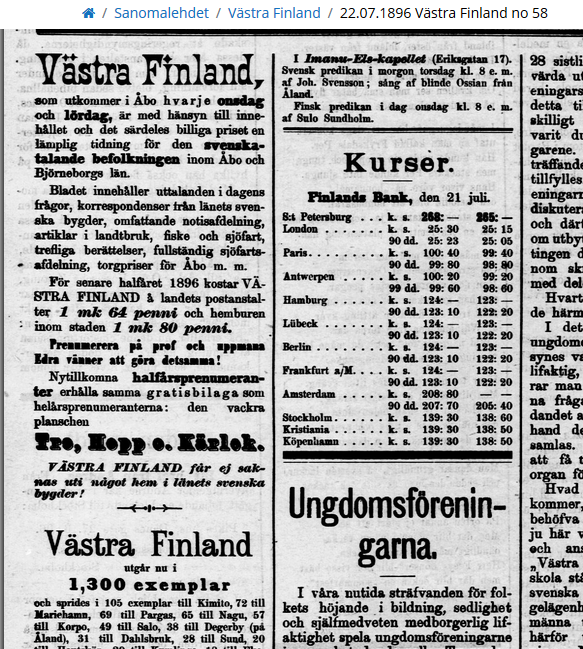

Västra Finland was aimed at rural areas, especially the archipelago, where mail was not distributed on a daily basis. This is how Västra Finland described its contents in 1896: The paper contains comments on daily matters, correspondence from the Swedish regions of the province, a wide-ranging advertising section, articles about farming, fishing and shipping, nice stories, a complete shipping section, and prices at the marketplace in Turku, among other things. The paper had a circulation of 1,300 copies at the time.

Figure 1. Västra Finland no. 58, 22.07.1896

Suometar was founded in Helsinki in 1847. It focused on finding the Finnish identity and developing the Finnish language. The name of the newspaper comes from the name Suomi (= Finland). When political texts were included in the paper, censorship authorities got worried. This was one of the reasons that led to the language decree of 1850, which allowed only religious and economic texts to be published in Finnish. In protest, Suometar stopped publishing for the rest of the year.

Suometar had correspondents around the country. This improved spreading of the press and made people feel that Suometar was their own newspaper. Their “letters from the countryside” section was a concept widely used by other Finnish-language newspapers.

Suometar was allowed to publish war-related news as the Crimean War reached the Finnish coast. Consequently, Suometar’s circulation grew significantly. In the late 1850s Suometar was one of the biggest newspapers in Finland and the leading voice of the Fennomans. In the 1860s it gradually lost readers to its competitors until it stopped being published.

A couple of years later, the Fennomans founded Uusi Suometar (uusi is a Finnish word for new) as their chief organ, which fought for Finnish to be acknowledged as an official language together with Swedish. Educating the population was also high on the agenda of Uusi Suometar. In terms of alcohol, religion and moral questions, Uusi Suometar was conservative.

Uusi Suometar expressed its stance on Russian policy rather moderately. In the so-called years of Russification, it was censored and cautioned many times, but it did not get banned.

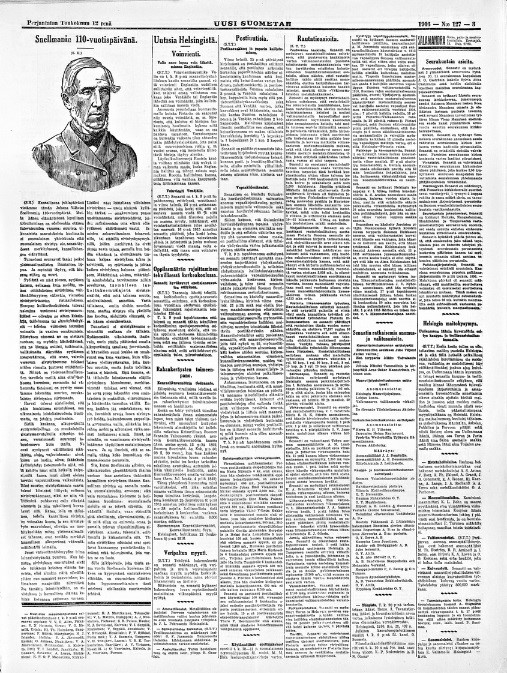

Leaning on its tradition as a national newspaper, Uusi Suometar emphasized democracy and Finnish identity. The following figure shows an editorial from the 110th anniversary of J. V. Snellman’s birth. Snellman was a philosopher, statesman and journalist, who had a great impact on the development of the Finnish language and public discourse in newspapers. According to the editorial, a lot was still to be done to fulfill his life’s work. It went on to say that we should not admire and adopt foreign cultures but consolidate our own Finnish culture and civilization.

Figure 2. Uusi Suometar no. 127, 12.05.1916

Sanomia Turustawas a Finnish-language newspaper founded in 1850 by J. W. Lillja, the publisher of Åbo Underrättelser. In its early years, it focused on religious texts and agricultural education. As soon as the publishing restrictions concerning Finnish language were lifted, Sanomia Turusta began to print news, and in the 1860’s it was the most widespread paper in the rural areas of Western Finland.

Politically, Sanomia Turusta was very cautious about expressing Fennoman ideology. On the other hand, Aura (later renamed Uusi Aura) – another Finnish-language, Fennoman newspaper in Turku - took an active part in the language battle.

On a lighter note, here are some clippings from Uusi Aura’s weather news. That’s right, there were no weather forecasts but facts about yesterday’s weather!

Figure 3. Yesterday’s weather in Uusi Aura no. 12, 27.01.1916, no. 37, 08.02.1916, no. 48, 19.02.1916 and no. 283, 07.12.1917

Hufvudstadsbladet has since its birth been a non-political newspaper with purely commercial goals. Its first editor August Schauman and his successor A. R. Frenckell introduced some Scandinavian journalistic ideas and practices to Finland. For example, Hufvudstadsbladet was the first Finnish newspaper which was delivered to the home. It gained a large readership among the Swedish-speaking inhabitants of Helsinki, and became a popular advertising medium. In order to broaden the circulation to also include outside of Helsinki, Frenckell hired a large number of journalists, added an agricultural section in the paper and started to build a network of foreign correspondents. In the 1890’s Hufvudstadsbladet had the largest circulation of all the newspapers in Finland. It has established itself as the most widespread Swedish-language title in our country, even today.

Figure 4. Advertisements. Hufvudstadsbladet no. 191, 19.08.1867

Päivälehti represented Fennomania, which focused on the rights of the Finnish language and nation. It was a liberal newspaper, and it strove for curing social ills. Many distinguished writers and artists contributed to Päivälehti, and it was one of the most important newspapers in Finland in the 1890’s. In 1899 - 1904, Päivälehti strongly defended the Finnish constitution against the Russification policy of the Russian empire. Due to this, its content was censored, and the whole paper was repeatedly shut down for a short period. Nikolay Bobrikov (the Russian covernor-general of Finland) dismissed the editor from his job and exiled him from the country.

Bobrikov was assassinated in June 1904. A week after this, Päivälehti published an editorial with the headline “Juhannuksena” (At Midsummer), rejoicing in the victory of light over the time of darkness. The censorship authorities understood that the editorial metaphorically referred to Bobrikov’s death, and hence Päivälehti was permanently shut down.

Helsingin Sanomat was founded to succeed Päivälehti. In its first year Helsingin Sanomat had to deal with censorship, and in the following years there were internal disputes among the Fennomans who published the paper. Since 1914, Helsingin Sanomat is published seven days a week. Today it is the biggest morning paper in Finland.

Newspapers have played an important role in Finnish history, and they have traditionally been highly valued in our thinking. Even today, Finns are avid readers of newspapers – both digitally and on paper.

References:

Tommila, P., Landgrén, L., Leino-Kaukiainen, P. & Kerkkonen, J. (1988). Suomen lehdistön historia 1: Sanomalehdistön vaiheet vuoteen 1905. Kuopio: Kustannuskiila.

Tommila, P., Ekman-Salokangas, U., Aalto, E. & Salokangas, R. (1988). Suomen lehdistön historia 5: Hakuteos Aamulehti - Kotka Nyheter : sanoma- ja paikallislehdistö 1771-1985. Kuopio: Kustannuskiila.

Tommila, P., Ekman-Salokangas, U., Aalto, E. & Salokangas, R. (1988). Suomen lehdistön historia 6: Hakuteos Kotokulma – Savon Lehti : sanoma- ja paikallislehdistö 1771-1985. Kuopio: Kustannuskiila.

Tommila, P., Ekman-Salokangas, U., Aalto, E. & Salokangas, R. (1988). Suomen lehdistön historia 7: Hakuteos Savonlinna-Övermarks tidning : sanoma- ja paikallislehdistö 1771-1985. Kuopio: Kustannuskiila.

https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/etusivu?set_language=en

https://www.britannica.com/place/Finland/The-struggle-for-independence#ref393144

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nikolay-Bobrikov

https://web.archive.org/web/20060708183728if_/http://www.sanoma.fi/historia/1889-1917.html

http://mediaauditfinland.fi/english/