NewsEyen blogia kirjoittavat tiimimme jäsenet. Blogissa tuodaan terveisiä konferensseista, pohdiskellaan ajankohtaisia asioita, kerrotaan projektin sisäisiä uutisia sekä esitellään tiivistä tietoa tapaustutkimuksistamme tai projektiin liittyvistä julkaisuista. Blogikirjoitukset ovat pääosin englanninkielisiä, mutta voivat silloin tällöin sisältää muutakin kirjoittajan suosimaa kieltä – olemmehan monikielinen joukko! Mukavia lukuhetkiä!

Curfew and inflammatory media coverage: spotlight on an exceptional measure

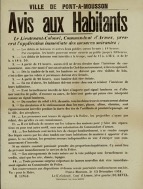

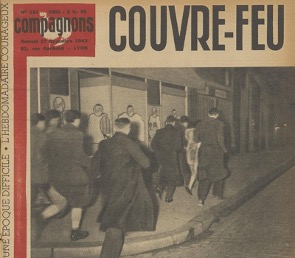

Compagnons: l’hebdomadaire jeune [“the young people’s weekly”, known at the time as l’hebdomadaire courageux d’une époque difficile – “a difficult era’s courageous weekly”], 27 November 1943

“We are at war, a health war of course. We are not fighting an army or another nation. But the enemy is here, invisible, elusive, and is advancing. And that requires us all to mobilise. We are at war. All action taken by the government and parliament must now focus on combating the epidemic. Day and night alike, nothing must be allowed to distract us”.

It was with these words that the President of the Republic Emmanuel Macron addressed the French people on 16 March last year in order to declare the implementation of a national lockdown designed to keep the COVID-19 epidemic at bay. The military metaphors that interspersed the President’s speech like a leitmotiv, along with the warlike rhetoric widely adopted by political and media actors, have associated and conflated armed conflict and health disaster. Although the appropriateness of this martial tone may be questionable, the analogy between population control mechanisms adopted in wartime and those activated in the context of the fight against the novel coronavirus may well be productive.

In addition to the initial home confinement decreed in March 2020, Emmanuel Macron announced a second measure on 14 October restricting movement, first of all in Île-de-France and eight metropolises under maximum alert and then in fifty-four départements: the curfew. This night-time restriction – which made its comeback on 15 December, taking over from the second lockdown – has awakened disturbing historical images in all of us, images of war and occupation. But what stories of curfews can we read in digitised copies of the newspapers and magazines of days gone by? Let’s dip into Gallica’s collections.

"The last ones up cover the fire"

Before it came to have its present threatening associations, the term “curfew” was employed in the Middle Ages to refer to a measure designed to prevent fire risks. As towns were essentially built of wood, it was necessary to ensure that their inhabitants did not go to bed leaving burning fireplaces unwatched. When night fell, the authorities rang one of the belfry’s bells to remind people that it was time to “put out fires”. But rather than putting them completely out, inhabitants covered them with cast-iron utensils in order to keep them safely alight. In those days, the curfew was an everyday event devoid of any serious or militaristic connotations. As Jean-Claude Schmitt points out in his book Les Rythmes au Moyen Âge (Paris, Gallimard, 2016) it was also a way of regulating “citizens’ lives by creating a separation between day and night”.

IBN BUTLÂN, Tacuinum sanitatis

The custom became widespread in the 13th century, with the development of the “watch”, which consisted of guard duty carried out by citizens responsible for sounding the alarm and for relaying the alert if a fire broke out. The night watch was also responsible for spotting and reporting brawls, thefts and assaults, as well as possible external dangers. Although it was a measure designed to maintain public order (and one that was to go into disuse during the French Revolution), it was not until the 19th century (with the provisions of the Act of 3 April 1878 amending the legal regime governing states of siege) that the term was militarised and became part of the defence arsenal. The curfew became associated with a strict prohibition to go outside during the night in periods of exceptional danger, as is evidenced in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, which added a military meaning to the term in its eighth edition

Eugène Scribe and Giacomo Meyerbeer, The Huguenots: opera in five acts, Paris, Maurice Schlesinger, 1836.

L.J-G Chénier, De L’État de siège, de son utilité et de ses effets, Paris: Librairie militaire, 1849.

Wars and occupation

1870-1871: the dark days of the siege of Paris

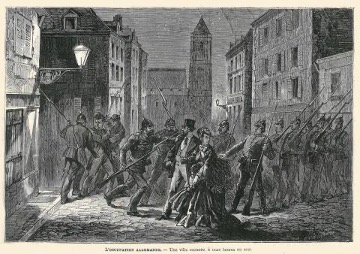

Jules Claretie, Histoire de la Révolution de 1870-1871, Paris, Librairie illustrée, 1877.

During the Franco-Prussian War, as Paris was surrounded by German troops, the newspaper Le Siècle suggested that a curfew be imposed in order to prevent real or supposed signals being sent by spies from attic windows to provide the enemy with intelligence information: “We request that the curfew be sounded at the close of day and that the inhabitants of Paris be obliged to close their shutters or curtains so that no light is to be seen anywhere” (Le Siècle, 23 September 1870). The proposal was not looked upon with favour by the editors of Le Temps daily newspaper, who deemed such a measure mean-spirited and inappropriate in the following day’s edition:

“Now we have Le Siècle suggesting that the curfew be sounded like it used to be in the Middle Ages. Was the rather strange measure taken by M. de Kératry with regard to cafés not enough? A measure good for nothing except adding to the difficulties and discomforts brought about by the siege. Must we now shut ourselves up in darkness in our homes? Will they not then forbid us to go out in the street after a certain hour of the day? We have forgotten that courage is contagious and that people take comfort when they are together. […] We do not understand why, on the contrary, an attempt is being made to make the already difficult existence of Paris’s defenders – most of them already separated from their friends and families – altogether unbearable.” (Le Temps, 24 September 1870)

Despite this outcry, Paris’s inhabitants, deprived of wood, gas and coal during the siege and in particular during the winter of 1870-71, were forced to accept living in a darkness reminiscent of the mediaeval curfew system. There was no lack of stories of life in time of siege in the press following the Franco-German Armistice, employing analogies to describe the precariousness of living conditions: “a huge blot of ink, a blanket of gloom invading squares, blocking streets and climbing walls. Just as we picture towns in the Middle Ages after the curfew had sounded. I have glimpsed passers-by on their way back home: lantern in hand, a sight no longer seen, even in the remotest of provinces.” ("Scenes of Siege Life ", Le Monde illustré, 4 February 1871)

First World War: curfew and war effort

During the First World War, it was the need to save money in order to support the war effort that led the government to take new measures. Hence, a curfew and then an annual time change suggested by Member of Parliament André Honnorat were adopted in order to help reduce energy consumption.

Le Petit Provençal, 16 April 1916

The curfew also involved in the closure of bars and restaurants, as well as the suspension of transport services in the evening, as can be seen from this article published in La Croix on 5 August 1914 :

“Curfew at 8 o’clock. — Paris’s Military Governor has decided that the Metro and all means of public transport must stop running at 8 o’clock in the evening. Cafes and restaurants must close at the same time. This decision will be applied from 4 August. Following the instructions I issued yesterday on the closure of licensed premises: Establishments that operate exclusively as restaurants, excluding coffee and soft drinks, are authorised to remain open until half past 9.” (La Croix, 5 August 1914, p.4/4)

Although similar measures were ordered across French soil, it was difficult to check that they were actually being applied and there were a number of disparities between regions, giving rise to a wave of protests:

“Our eminent contributor M. Engerand, Member of Parliament for Calvados, has sent the following letter to the Prefect of his département: Langrune-sur-Mer, 15 August. Dear Sir, the Paris newspapers claim that you can dance, even the tango, at the Deauville casino until late at night; other information that I have received confirms that casinos on other beaches stay lit up very late at night, while the curfew is sounded at 9 p.m. in our quieter resorts. Such waste, contrary to these restrictions, should be seen as intolerable; in the absence of my colleagues and friends Plandin and Blaisot, who are currently at the front, and sure of being the spokesman for all of Calvados’s representatives in Parliament, I strongly protest and, in the event of such scandalous behaviour being proven, ask you to put an immediate end to it. I urge you to remind the managers of such establishments that we are at war.” (L’Écho de Paris, 17 August 1917)

A good many newspapers criticised the half-measure and inconsistency of government decisions that required small business to close while large establishments were allowed to stay open:

The sole criticism we shall make of the decision that has just been taken with regard to shop closing times is that it seems to us to be a half-measure. How so? Many small traders who consume the minimum possible quantities of light will see their businesses curtailed even though they are a public necessity […] Cobblers will have to close but “tea houses” will be wide open to accommodate “these ladies” because tea is classified as food”. (La Libre Parole, 9 November 1916, p. 2)

Such debates are reminiscent of current polemics on the closure of so-called “non-essential” shops while supermarkets and eCommerces can continue doing business – with the difference that, in 1916, entertainment and cultural venues such as cinemas and the Opera remained open.

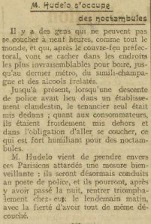

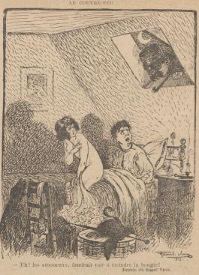

The individualism and indiscipline displayed by the French public, some of whom seemed incapable of complying with the curfew, were also mocked in the humorous press, as is evidenced by this article published in L’Œuvre on 18 October 1917 (p.2).

Le Rire 2 December 1916, p. 9/12

Second World War: the occupant’s instructions

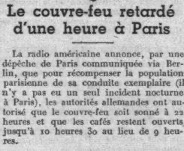

Although the press of the interwar period mentioned curfews implemented in Bombay, Shanghai and Palestine, it was not until the Second World War that the measure made its reappearance in France and in England – this time under the name of blackout, a passive anti-aircraft defence strategy. A curfew was enacted in the capital at the very beginning of the occupation, with adaptable hours depending on how the population behaved and any unrest that needed to be controlled. Hence, La Croix of 10 July 1940 reports that the German authorities had set the curfew and cafe closing time at a later hour in order to “reward the Parisian population for its exemplary conduct” – should we infer from this that the resetting of the curfew from 9 p.m. to 8 p.m. was punishment for the French public’s bad behaviour in the face of the viral occupant …?

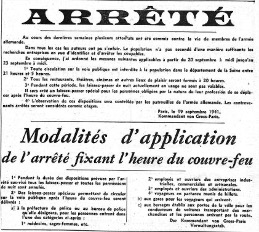

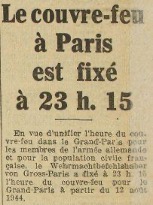

The curfew, shifted to 11 p.m. in October 1940 and to midnight the following month, was applied in disparate fashion across the country, depending on the emergence of pockets of resistance. In 1941, with attacks increasing in the Paris region, Kommandant von Gross deemed that the population had not done enough to help find the guilty parties and issued an order designed to control movement.

The tightening of security measures was the subject of a number of reports in the press. In an article published inL’Œuvre of 21 September 1941, its author cast doubt on the ability of Parisians to adhere to the rules in force, given their reputation for rebelliousness. In the end, there were no outbreaks of unrest to speak of, this time at least. In 1942, it was the Jews living in the occupied zone who were above all targeted by the curfew. On 12 February,the daily newspaper France reproduced the following communiqué: “The Commandant of the occupying forces in Paris has just issued an order under which ‘Jews are prohibited from leaving their homes between 8 o’clock in the evening and 6 o’clock in the morning, and from changing their place of residence. Any contravention of the order’s stipulations will make its perpetrator liable to a fine, imprisonment or internment in a Jewish concentration camp.’”

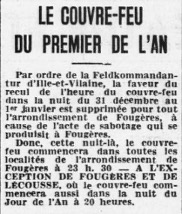

Finally, from 1943 onwards, the curfew was applied across the country following increasingly determined action on the part of the Resistance, and was to remain in force until the end of the war.

L’Œuvre, 12 August 1944

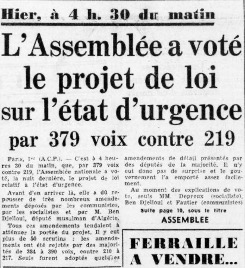

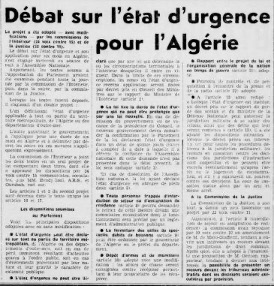

Curfew and the Algerian War: creation of the state of emergency

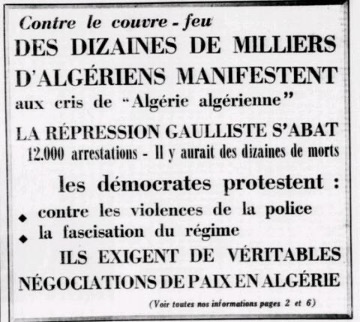

On 3 April 1955, the law imposing a state of emergency was adopted and then applied on three occasions during the Algerian War, in the hope of dealing with attacks by the National Liberation Front. The curfew was first enacted in order to keep watch on Algeria’s Arab population and facilitate arrests. A few years later, in October 1961, Paris Police Prefect Maurice Papon used the measure to target “French Muslims of Algerian origin”, who were prohibited from leaving home between 8:30 p.m. and 5:30 a.m., as well as congregating and managing or patronising bars after 7 p.m. On 17 October, a demonstration by thousands of Algerians protesting against these discriminatory restrictions resulted in a bloody crackdown by the French police.

Hence, the curfew, once a simple preventive measure later used as an economic solution and then as a liberticidal instrument of Nazism and stigmatisation, became symbolic of our history’s darkest hours.

Journal du Canton d’Aubervilliers, 21 October 1961

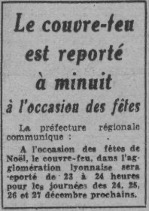

On 17 October 2020, some seventy years after the tragic events of 17 October 1961, the curfew was adopted once again, this time to combat the viral threat and in the context of a special legal system created in March 2020 – “the state of medical emergency”, with exemption on 24 December for Christmas Eve but not for New Year’s Eve. We can only hope that peace will soon be made with our viral enemy. And as for knowing whether 2021 will be a brighter year, the best way of finding out is still by consulting the oracles…